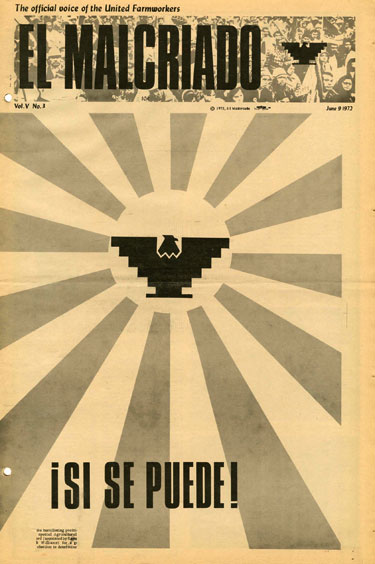

¡Si Se Puede!

Yes We Can!

Remembering Cesar’s 1972 Fast...

by

Christine Marin, Ph.D.

Archivist and Historian of the

Chicano/Chicana Research Collection,

Arizona State University

I want to tell you about events that occurred in 1972: events that created change in the ways we see ourselves now, and in the way that others see us. Within a twenty-four day period, from May 11 to June 4, 1972, I was a witness to historical events events so inspiring, they have remained with me. I share them with you now...

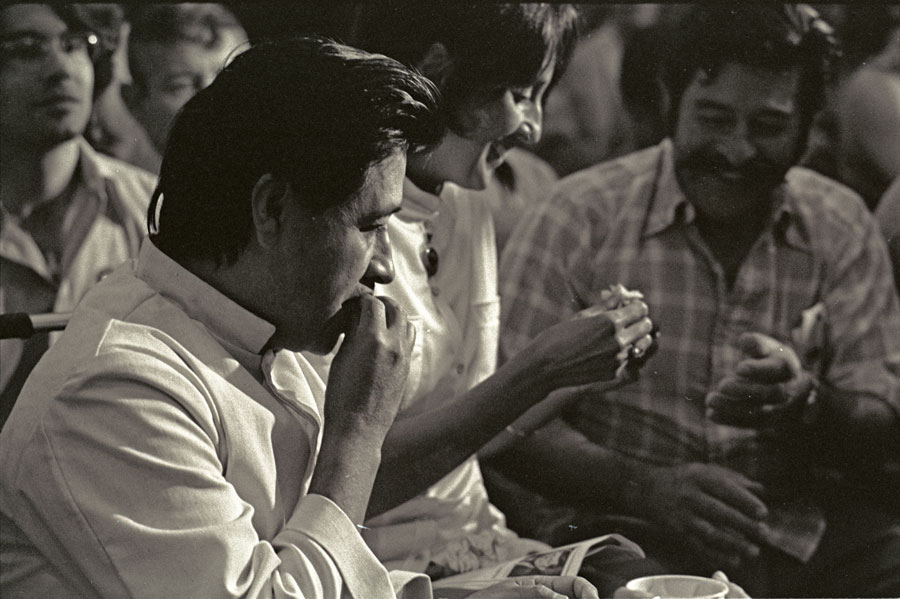

Cesar Chavez breaks his fast, with Joan Baez and

Alfredo Vasquez

photo credit: Glen Pearcy

On May 11, 1972, the Arizona legislature passed a Farm-Bureau sponsored bill, that restricted collective bargaining, and outlawed boycotts and strikes at harvest time. Cesar Chavez and the UFW hoped that governor Jack Williams would veto the bill, but he didn’t.The next day Cesar Chavez began a fast to call attention to this bill. His aides tried to convince him that his campaign against the arizona law was futile, and that he shouldn’t fast. They argued with him, saying, “Cesar, no se puede, no se puede,” ..and he would say, “Si, si se puede,” Yes, it can be done.”

Santa Rita center became the UFW’s headquarters, and word got out that Cesar was fasting there, and that nightly masses were being held. I was among the many who wanted to see him, to hear him speak, to be in his presence. I had read so much about him, seen his picture on farmworkers’ posters, knew about the grape boycott and supported the UFW’s efforts to organize workers in Arizona. I helped chicano students distribute “boycott lettuce” leaflets at Safeway. In my eyes, Cesar Chavez stood ten feet tall.

And so I went to the Santa Rita center. I went often. This is what I saw. Large crowds packed the Santa Rita center, eager to catch a glimpse of the man who had dared to challenge Arizona’s governor. Farmworkers and their families from throughout the state came to attend the nightly masses. There were rugged-looking men, many with sunburned faces. They were working men… their shirts open at the collar, their sleeves rolled-up. The women were dressed in simple, no-frill dresses, many wearing blouses and skirts. Little girls held candles. Metal chairs were arranged in rows and rows, filling the hall, and every chair was filled. People stood along the walls, hugging every inch of space. When father Joe Melton blessed the wine for the sacrament, he told us that this was no ordinary wine, but wine harvested by men and women, working in dignity, under the protection of a union contract. The hymns sung at the mass were union hymns, in English and Spanish. I searched the crowd, looking for Cesar Chavez, my eyes were everywhere... I saw Gustavo Gutierrez, Arizona’s UFW representative; state representative Lito Peña was there; Ricardo Chavez, Cesar’s brother, Sister Mary Rose Christy, Joe Eddie and Rosie Lopez; Jim Rutkowski, the UFW attorney; ASU students were in the crowd.

Then a silence settled the room, as a group of people entered the hall from another room. You could hear a pin drop, and a short, small, weary-looking man appeared. He was helped to his chair by others, their arms around his elbows and wrists. I wasn’t sure what was happening. I didn’t know who they were. “Where is Cesar Chavez,” I asked myself. “Is that him,” I wondered. No one said a word. No one announced his presence. There was no podium where he could speak. I expected to see Chavez address the crowd. He walked, ever so slowly, to the chair, steadying himself against the men so that he wouldn’t fall. There was no voice from a microphone announcing his arrival, no applause from the crowd, just silence.

It was like that almost every night. Cesar didn’t speak, but the crowd was satisfied just to be in his presence, to hear mass with him. One evening, May 20, Senator George McGovern came to see Cesar at Santa Rita. He interrupted his presidential campaign to be at the mass with him. On May 30, the 19th day of the fast, Coretta Scott King came to Santa Rita and attended mass with Cesar. She spoke to the crowd about her husband, and said how much she admired Cesar’s philosophy of non-violence, so much like Martin’s, she said.

Cesar looked weaker. The day after Mrs. King’s visit, doctor Augusto Ortiz ordered Cesar to be taken to the nearby Memorial Hospital. We learned later that Cesar had an erratic heartbeat, that his uric acid level had risen, and that he was feeling the effects of the fast.

But he refused to end his fast. His health worsened. On June 4, 1972, after twenty-four days, Cesar ended his fast at a memorial mass held in the memory of Bobby Kennedy, the president’s beloved brother. Joe Kennedy, and his brother, Michael, Bobby’s sons, were with Cesar at the mass. Cesar was too weak to speak, but someone read his statement, saying that the fast was meant to show the suffering among farm workers.

The fasting debilitated Cesar Chavez somewhat; but it also gave us strength and courage that we had not had before and infinite patience and never-ending persistence to overcome any obstacles. That may be his legacy to us: that we remain steadfast in our own convictions to overcome injustice and poverty, and never give up — because a people united can never be defeated.... Si Se Puede.